The Tallest Tower

Development Blog

A Good Toy

To design a good puzzle, first build a good toy.

-Scott Kim

In puzzle game design, it’s useful to consider how a puzzle or mechanic behaves as a toy.

You can evaluate a puzzle game’s toy by examining how the game would play with the levels and goals removed. Throw the player in a barebones stage with no objective. Is this still enjoyable? Interesting? What can they learn and discover just from playing around? How satisfying is this process?

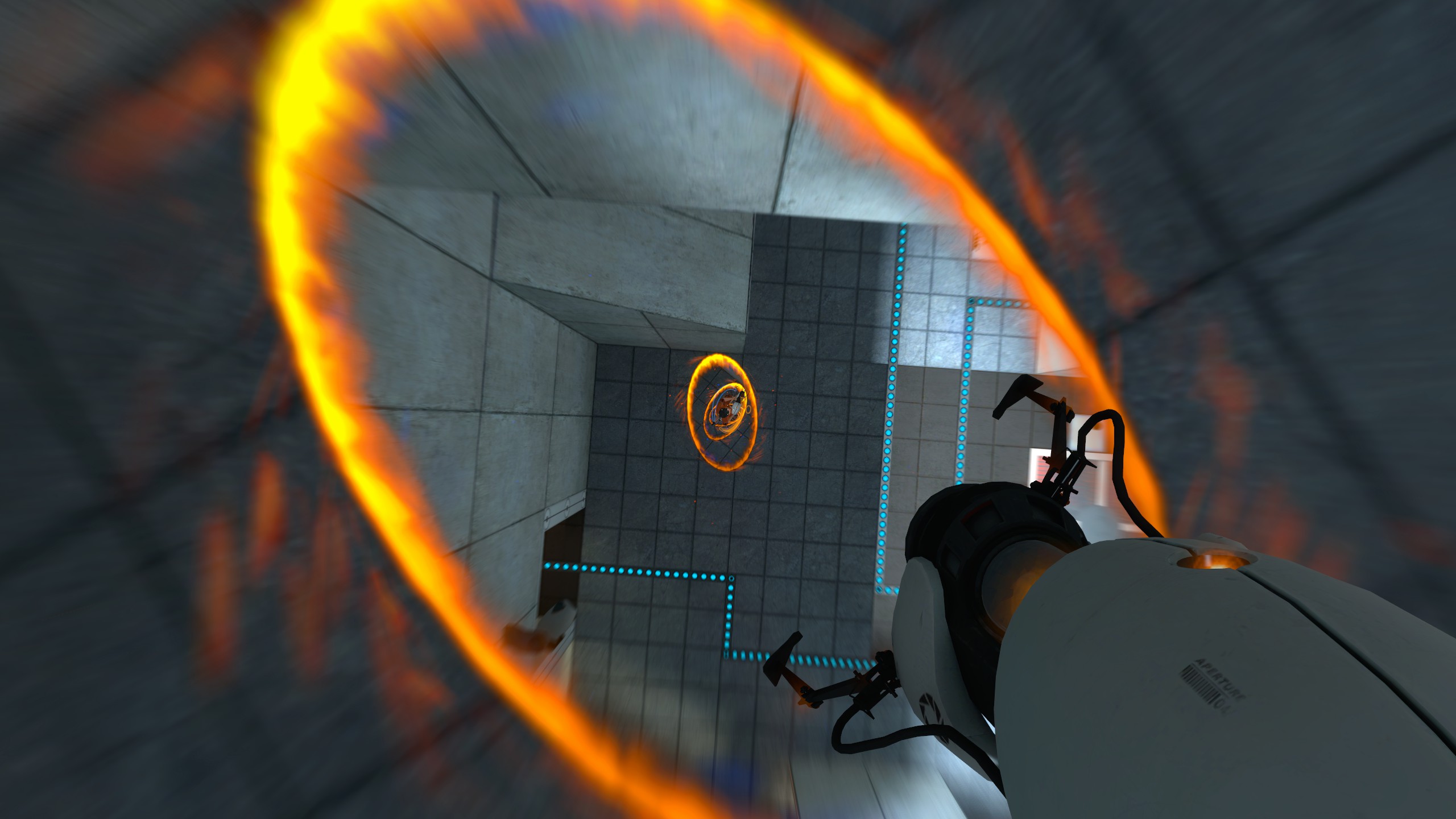

Think about what this looks like for a game like Portal. In an empty level, you could place one portal on the ceiling and another on the wall in front of you, look down at yourself, then walk through the portal and drop down to where you just were. You could place one in the floor and one on the ceiling and fall forever. Devoid of an objective, Portal’s mechanics are still a joy to tinker with.

Now contrast this with Stephen’s Sausage Roll. In an empty level, you could move some sausages around with a fork. Maybe you figure out you can spear a sausage by pressing it against a wall. Stephen’s Sausage Roll is a fantastic, meticulously designed game. But its mechanics don’t have the same toy-like properties as Portal.

The quality of a puzzle’s toy seems to correlate with how ‘mind-bending’ the central mechanic is. When I solve a puzzle in Portal, I feel like I’m breaking the laws of the universe. Like I’m wrapping my mind around a new way of thinking. When I solve a puzzle in Stephen’s Sausage Roll, I just feel really smart. Still great, but not quite the same.

A puzzle’s toy also makes the difference between an enthusiast puzzle game and one with mainstream appeal. This distinction isn’t just the difficulty of the puzzles. An enthusiast puzzle game often has puzzles and nothing else, puzzles based on mechanics that wouldn’t be much fun to experiment with devoid of a goal. A puzzle game with mainstream appeal can be just as challenging and explore mechanics and ideas the same way, but is practically required to have a good toy.

Put another way: A good toy means a good hook.

Below are a few puzzle games I’ve played, evaluated for how they function as a toy. I’ve picked exclusively outstanding games here, and for a reason: I want to evaluate the quality of the toy independent of the quality of the puzzles. A good toy is far from the only factor in making a great puzzle game, and there are many phenomenal puzzle games with bad toys. But my hope here is to hone this specific lens so we can evaluate our own ideas and make the best possible toys for our games.

Portal

Portal is the best example of a toy I know of. Throw a player in an empty room with a portal gun, and they will immediately start experimenting and trying to wrap their head around it.

Much of the appeal of this toy hinges on some key details:

- The game plays in 3D first person

- You can see through placed portals

- Movement is continuous and momentum is conserved between portals, as if a rift between the two locations in space truly exists

Remove any of these details and it becomes significantly less mind bending:

- 2D Portal exists, and it’s much less viscerally interesting to play with.

- Half the joy of portals is peeking through to the other side and seeing what’s there, or seeing yourself from a different angle. Remove this, and suddenly the two locations in space don’t feel seamlessly connected. You can set Portal Render Depth to 0 in the settings to get a feel for how much less satisfying this is.

- If the ability to look through portals makes them visually convincing, then conservation of momentum makes them physically convincing. It also makes entire classes of interesting puzzles possible (for example, flings).

Stephen’s Sausage Roll

Stephen’s Sausage Roll doesn’t have a good toy. Pushing around sausages isn’t intrinsically interesting, and the game doesn’t provide notably pleasing aesthetics for doing so. That aside though, it’s a painstakingly designed game that deeply explores the mechanics of this sausage-pushing through a gauntlet of challenging puzzles, which all told took me around 50 hours to complete.

These are classic traits of an enthusiast puzzle game: Amazing puzzles, mediocre hook.

Braid

Braid’s time travel mechanics are a great toy. The passage of time is something we’re all innately aware of and spend plenty of time pondering, and this real-world contextualizing helps its appeal as a good toy. Many of us have discussed with friends or enjoyed fiction about concepts like time travel.

Like Portal, the toy-like feeling of Braid’s mechanics also lean on its aesthetic presentation. Remove the reversed music and the visuals of rewinding objects, and you lose some of the effect. Remove the fluidity and seamlessness of rewinding, and you lose even more.

In the worst case, imagine playing Braid with YouTube-style rewind controls: pressing the left arrow suddenly snaps you one second into the past. This is a much worse toy. The rewinding no longer feels as fun to play around with, even though you could still solve the puzzles like this.

We’re seeing an interesting pattern emerge: The presentation of a mechanic plays a significant role in how good a toy it makes. This isn’t too suprising. But it does help us understand that a good toy doesn’t just come down to the core concept. That concept must also be supported by good execution and visceral communication of the idea.

Snakebird

Snakebird centers around moving several creatures in a manner similar to the classic game Snake, but with gravity. Many interesting consequences emerge from this, but much like Stephen’s Sausage Roll, moving these snakebirds around without a goal is fundamentally not all that interesting.

Antichamber

Rather than having one central toy, Antichamber is more a collection of different toys around a central theme. Some of these toys are fantastic, like the non-euclidean geometry, or the world changing depending on where you look. Some are less so, like the cube gun.

The Witness

The line puzzles in The Witness aren’t a particularly good toy. There’s some toy-like nature to the puzzles with more environmental aspects as you push further into the game, but it’s still minor.

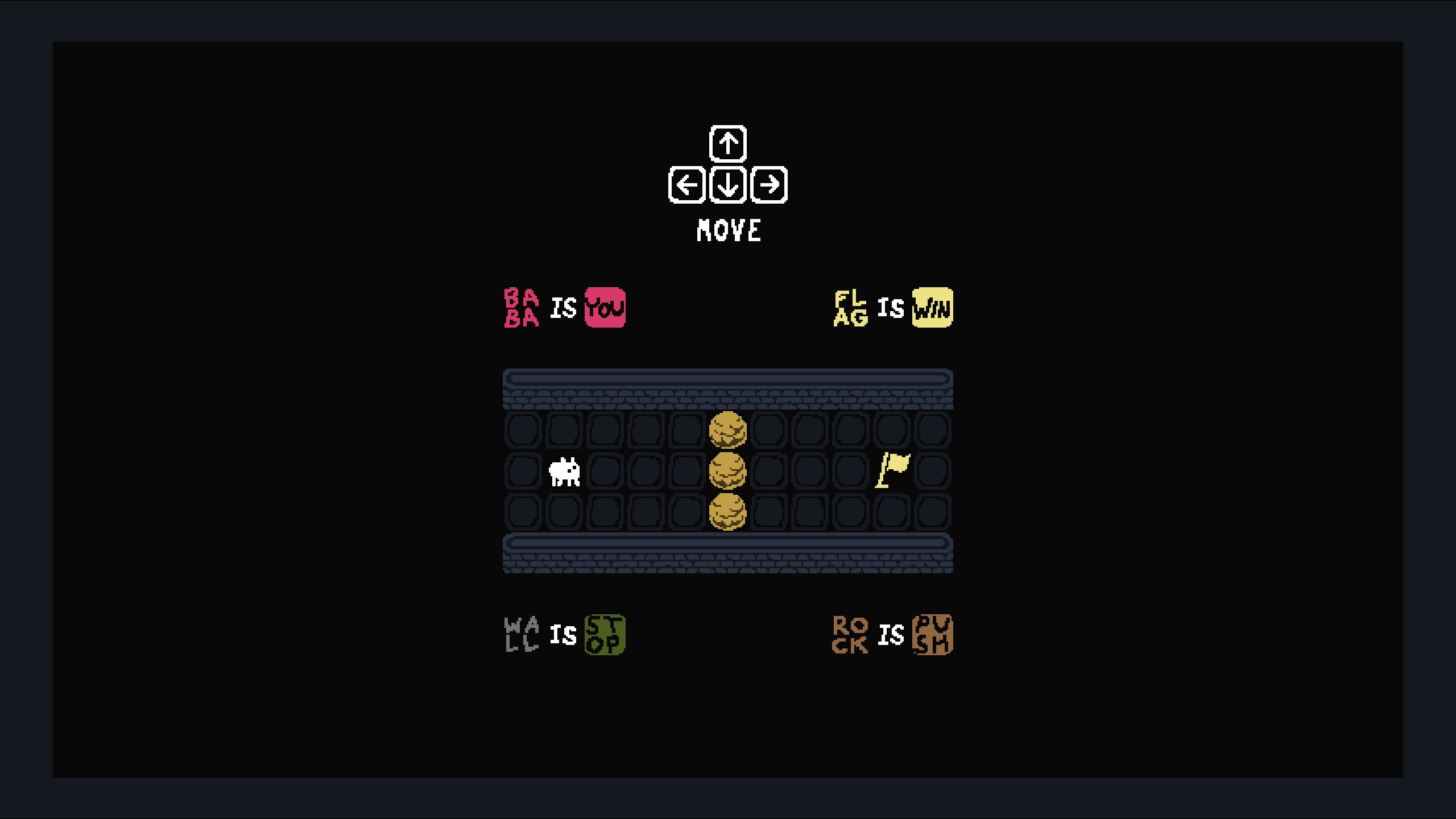

Baba Is You

The very first level in Baba Is You drives home how good a toy it is. You control Baba with the arrow keys, and to pass this level you just need to touch the flag. Easy enough.

But you’ll probably play around a little first. You might disconnect Wall Is Stop, and realize you can now walk right through the wall. And then you might connect Wall Is You and Baba Is Win, and suddenly you’re moving around the level as the wall, and you win when you make the wall touch Baba. This first level is basically the empty level test I described above, and it passes with flying colours.

Remarkably, Baba Is You is creates an outstanding toy with zero reliance on aesthetics or specific visual effects. The previous examples of good toys all rely at least partly on visuals, but Baba Is You proves that fancy visuals are not a requirement for a great toy. The mechanics interact in unexpected ways, and it’s the surprise of turning into a wall, or suddenly filling the entire level with Babas (and winning!) that makes this toy delightful.

Takeaways

-

A good puzzle game greatly expands its appeal by having a good toy.

-

A good toy is a good hook.

-

A good toy usually isn’t something you can polish out of an existing game. You must be evaluating your toy from the start, as the nature of the toy is at least partly intrinsic to your core concept.

-

Effective toys have some combination of:

- Plentiful and delightful surprises.

- Contextualization to our lived experience. The more fundamental and relatable the mechanic is to our understanding of the world (eg. space and time vs. how snakebirds move on a grid), the better.

- An effective presentation to let us viscerally experience the nature of the ideas we’re exploring.